Books

Why 'Daughter of Two Rivers' Is More Than Just Good Historical Fiction

Ratul Chakraborty

Jan 15, 2026, 10:00 AM | Updated 10:05 AM IST

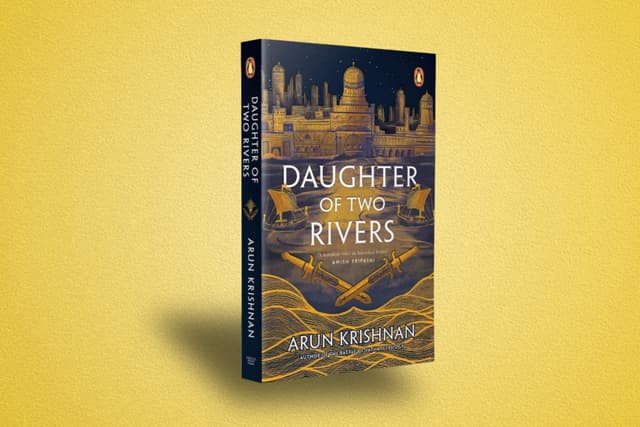

Daughter of Two Rivers. Dr Arun Krishnan. Ebury Press. Pages: 304. Price: Rs 275.

I write this when the times are unquiet and feverish. Shadows old and new creep across the map, both in our neighbourhood and beyond the oceans near and far. As we watch on, all notions of compassion, honour and virtue are made sacrificial offerings to the altar of realpolitik and Matsanyay, an era of helpless acceptance that might is right. Was it always thus?

The world of Arun Krishnan's Daughter of Two Rivers (Penguin, 2025) reveals a tantalising echo of this present reality. Set four thousand years in the past, it traces the journey of an impoverished Indian prince, Arjuna, to the fabled lands of Babylon. This basic structure allows the author to invoke themes that are startlingly current: the life of an economic migrant to a cosmopolitan melting pot, the unstated anxieties and shifting loyalties during the liminal period of a fundamental tech transition, and the irrevocable impact of climate change.

On such a backdrop we witness a tale that is highly entertaining. Arjuna is a hero who is easy for the reader to fall in love with, and Lilith, the other protagonist, is one of Krishnan's finest creations. Their chemistry is undeniable, and together they drive the plot forward through a variety of alarums and excursions of increasingly higher stakes.

However, this book is so much more than its plot. It is very rare for an author to capture a sense of place and time with the warmth and fidelity that Krishnan demonstrates here.

Of course, readers of his previous works would be aware of his undeniable craft in this matter. However, in Daughter of Two Rivers, Krishnan steps out of the familiarity of medieval India into the relative unknown of the high antiquity of the river civilisations of Saraswati-Sindhu and Euphrates. In doing so, he shows us a world rich with lore and wonder and life, filled with delicate details and grand, sweeping panoramas.

Then there are the things which are unstated yet very much present in the larger narrative arc.

Arjuna embodies the spirit of a young India that has all too often been denied space in postcolonial English literature. He is kind and curious, resourceful and hardworking, valiant and risk-taking, respectful and passionate. In short he is everything that is absent in both the weak, ugly, loser Indian man pushed by the leftist cultural discourse or the toxic, hyper-masculine demigods of the desi silver screen.

Krishnan also brings to light that technology, more often than not, flowed out of India to the world. This is an undeniable historical fact which has been largely neglected thus far, wilfully or otherwise, in the popular creative space.

Indians, by and large, have been conditioned to believe that they are and always were a technological backwater, whether in an age where one can pay for fuchka with UPI or in an age where Indian smithies unlocked the secrets of iron and steel. The author deserves credit for making this one of the fundamental plot points in the book.

Finally, in Lilith we have an extraordinary examination of the diaspora experience: what does loyalty mean? Where do I truly belong? Where is home? What is home?

Above all, like all great storytellers, Krishnan tries to answer the most fundamental question of all: Who am I?

Both Arjuna and Lilith struggle as their sense of self gets shattered time and again by the events of the story. It is only at the very end that they accept the whole of themselves without holding back. This journey of self-acceptance forms the emotional core of this book, and the conclusion the author offers is simply masterful. The bittersweet aftertaste remains long after you have finished reading.

I found Arun Krishnan's Daughter of Two Rivers to be a refreshing tale of hope and romance amidst the cynical de facto transactionalism of our zeitgeist, exactly what the doctor ordered, establishing solid counterpoints to the cultural stereotypes that have been entrenched in the Indian mindspace for far too long.

History is kept alive among the masses through stories, and it is the dharma of the storyteller to create, through his art, the means to transmit truth across generations. Daughter of Two Rivers is a worthy addition to the distinguished lineage of works that fulfil this highest of duties.