Books

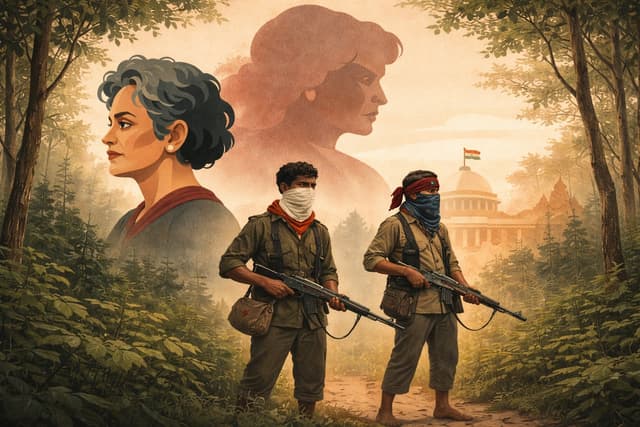

How Maternal Abuse Shaped Arundhati Roy's War Against India

Bholenath Vishwakarma

Jan 10, 2026, 07:30 AM | Updated 07:59 AM IST

In her much-awaited memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me, Arundhati Roy writes, "Once you've had a rocky and unsafe childhood, you can't trust safety. I learned early that the safest place can be the most dangerous. And that even when it isn't, I make it so."

This poetic assertion makes me wonder: is this why she feels that democratic India and the Hindus who have kept it secular are unsafe for her? And why, even if they were, she would 'make it so'.

Arundhati Roy needs no introduction, whether for her writing or for her support of violent, gun-toting men—be they Kashmiri terrorists (often labelled 'militants') fighting for Azadi, or Naxals fighting for land rights against exploitation by the government and corporations.

But her mother needed an introduction.

I would say this introduction was much-needed to understand Ms Roy's psychology. After reading the account of her 'abusive' mother—an odd name, as the biblical Mary is the epitome of love and sacrifice—and her absent father, it becomes clear why she developed an insecure, disorganised attachment pattern. This is reflected in the men she supports publicly and her hatred of India's economic liberalisation, democracy, corporations, and Hindus.

Ms Roy is a charmer. She speaks in a slow, trembling, empathetic voice—often with an abject naivety and a disregard for facts—that enthrals listeners who pay attention only because she is India's most famous Booker Prize winner. This fame persists largely because many are unaware of the two earlier winners: Ruth Prawer Jhabwala (1975) and V.S. Naipaul (1979).

Observe her body language: it is always evasive, as if she fears someone, and she projects a cultivated persona of vulnerability through an almost pleading tone. It is as if her mother's ghost is lurking behind her; Freud would have loved to have her on his couch.

There was merit in her winning the Booker Prize, even if one discounts the concerted lobbying from her coterie and the West's fascination with a recently liberated India. What stands out singularly in The God of Small Things is her lyrical, scintillating prose, rich with evocative adjectives and metaphors.

Ironically, in defiance of the conventions of non-fiction reportage, she employs these same literary devices to sway naive readers whilst providing little factual depth. Her essays are filled with such heavy rhetoric that Socrates would have despaired at the lack of logic, and Nabokov and Updike would have found her prose over-embellished for the truth.

The Pied Piper of Gen Z

Arundhati Roy relies heavily on the Rule of Three (or Tricolon and Hendiatris—the use of three parallel words, phrases, or clauses to make a point more passionate). Her non-fiction is filled with tricolons and parallelism that build empathy and create a sense of urgency to hammer home a political point.

Some examples of Roy's use of three parallel infinitives (to verb) are as follows:

"Above all, to watch. To try and understand. To never look away. And never, never to forget." In the essay The End of Imagination (1998). Similarly, in The Cost of Living (1999), she writes, "To love. To be loved. To never forget your own insignificance. To never get used to the unspeakable violence and the vulgar disparity of life around you."

She also employs the "Tricolon of Despair" (rhetorical questions), as seen in The End of Imagination (1998), "What shall we do then, those of us who are still alive? ... What shall we eat? What shall we drink? What shall we breathe?"

In Capitalism: A Ghost Story (2014), she uses a "Triad of the Oppressed": "The millions of landless people, the majority of them Dalits, Adivasis, and Muslims, driven from their villages..." and "Tidal waves of money crash through the institutions of democracy—the courts, the parliament, as well as the media..."

From Walking with the Comrades (2010), "...people who go to battle every day to protect their forests, their mountains, and their rivers..."

These books and articles are written in a language designed to inflame passion rather than to elicit serious debate. They are aimed at general readers who may struggle to glean facts from world events, or those who do not read newspapers regularly.

For a journalist or a serious reader, this prose is akin to a Mills & Boon novel; it is no surprise that her appeal seems strongest amongst younger demographics and those moved by the emotive, 'human interest' style of storytelling common in popular fiction.

The Goddess of Small Things

Now, let us recap how she became famous and what she has done to remain relevant post-Booker Prize. Her 1997 novel, The God of Small Things, is undoubtedly beautifully written—even if one disregards the theme of incest (which many foreign readers mistakenly believed was a common occurrence in India).

Following that success, she wrote no fiction for twenty years. In an interview with The New York Times, she remarked: 'I've always been slightly short with people who say, "You haven't written anything again," as if all the nonfiction I've written is not writing.'

Hence, she turned to activism. She has consistently been anti-government and anti-corporate, successfully turning an 'anti-India' stance into a brand. She earned over a million dollars in royalties from her debut novel—a feat that would have been impossible without the very forces of globalisation and corporate capitalism she so vehemently decries.

In 1997, few individuals outside the corporate world earned such wealth simply by sitting at a writing desk. According to her, economic liberalisation was ruinous for India; in the introduction to Listening to Grasshoppers: Field Notes on Democracy, she writes that 'the Congress opened up India's markets to international finance and sowed the seeds of the country's long-term ruin.' She rejects the capitalist vision of India, arguing that it fails the common people, particularly the poor.

First, she opposed the Narmada dam. India was not only impoverished, but in the 1990s, roughly 65 per cent of its population relied on agriculture for their livelihood. For water-scarce states like Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, the dam was a boon.

Furthermore, as a source of renewable energy, hydropower offered a sustainable solution that addressed climate change concerns long before they became a mainstream issue. However, in her opposition, she relied heavily on 'Poetic Politics' over 'Pragmatic Policy'.

Next, she opposed the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government for conducting nuclear tests in 1998. In her essay, The End of Imagination, she labelled the tests a sign of Hindu nationalism—ignoring the fact that the nuclear programme was initiated by the Indian National Congress under the aegis of Indira Gandhi. She further disregarded political realism and the reality that a nuclear-armed and openly belligerent Pakistan has been a clear, present, and imminent threat to India since its inception.

In recent decades, she has become best known for her support of the Kashmiri Azadi movement. However, she consistently fails to mention—let alone show concern for—the hundreds of thousands of displaced Kashmiri Pandits, thousands of whom were raped and murdered by proponents of that very same 'freedom' struggle.

For lack of any revolutionary act in a modern, fully satiated capitalist democratic country like India, the Naxal movement was the last romantic refuge that gives an orgasm to anyone and everyone coming out of a university after studying Marxist theory in their humanities classes. And Ms Roy would have been the last one expected not to join it.

And so, she supported the Naxals and wrote books and articles after travelling with a red bandana tied on her head to the hinterland where even the military dared not venture.

Surprisingly, whilst she never fails to attack Narendra Modi, the BJP, and the RSS with loaded terms like 'Hindutva', 'Fascism', and 'Saffron Brigade', she is remarkably silent regarding the Congress Party's role in the issues she decries.

She rarely, if ever, mentions that the Narmada Dam was a Rajiv Gandhi-era project, that economic liberalisation was a Congress initiative, or that the draconian Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act (AFSPA) of 1990 was enacted under a Congress government. She pointedly avoids attributing these policies to the party that actually authored them.

AFSPA was originally enacted by the Parliament of India in 1958. Successive governments, including those led by the Congress party, have maintained or extended its application in conflict areas. But rather than mentioning Congress she consistently blames the ambiguous "Indian state" and the "military occupation." Few individuals within India have criticised the armed forces as harshly as Ms Roy, with some comparing her rhetoric to that of the Pakistani state.

In her 2011 article, 'When corruption is viewed fuzzily', she links rampant corruption under the UPA government not to the Congress Party, but to the policy framework of 'liberalisation, privatisation, and globalisation'.

Psychological Scar of Mother Mary

"She was my shelter and my storm... She was woven through it all, taller in my mind than any billboard, more perilous than any river in spate, more relentless than the rain."

"When it came to me, Mrs Roy taught me how to think, then raged against my thoughts. She taught me to be free and raged against my freedom. She taught me to write and resented the author I became."

"I left my mother not because I didn't love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her. Staying would have made that impossible."

The trials and tribulations of Ms Roy, as recounted in her book, are a treasure trove for any psychoanalyst. Sadly, her female readers are only moved by what she suffered and disregard the mother and the impact she had on her.

In the liberal post-modernist universe, the perpetrator is always excused and instead, the victim is bestowed with empathy—a classic template. Whilst she herself forgot the victims of Islamic jihad—the Kashmiri Pandits—and showered all her empathy and fame on the Islamic perpetrators, it is a striking oddity.

The book sheds light on Attachment Theory and Paternal Deprivation. Roy's description of her "wild, imperfect, fatherless life" is more than just poetic imagery; it is a confession of psychological wounding. The "scars and cuts" she carries are the physical manifestations of a childhood devoid of structure and paternal security.

From a clinical perspective, such a void often leads to a disorganised attachment to authority. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that she gravitates towards men defined by violence and insurrection. These figures may represent a distorted effort to fill the paternal vacuum, replacing the absent father with the romanticised "revolutionary."

A Freudian analysis of Roy's fatherless upbringing suggests an unresolved Electra complex, wherein she seeks out male figures who embody the power or protection she lacked as a child—even when those figures are inherently dysfunctional. Freud might argue that her attraction to violent insurgents reflects a subconscious drive to resolve unmet needs for paternal attention, albeit in a highly maladaptive way for a romanticised revolutionary figure.

Experiencing severe abuse from her mother during childhood likely had profound effects on her emotional and psychological development. Such trauma often leads to chronic low self-esteem, difficulty in emotional regulation, and significant challenges in forming healthy attachments. The absence of a nurturing maternal figure may have left her perpetually seeking validation and security in external, often radical, spaces.

She has externalised her childhood trauma—the abuse by her mother and the absence of a stable father figure—into her political worldview. The adage 'the personal is political' fits her perfectly; a childhood spent resisting a domestic 'tyrant' has conditioned her to view all centralised power, specifically the State, as inherently tyrannical.

Having been so deeply terrorised as a child, she may have developed a passive-aggressive defence mechanism. This would explain why she maintains a soft, trembling voice even whilst advocating for the violent cause of Jihadis and Naxals.

For Roy, the Indian State—acting through entities like the Narmada Valley Development Authority—is the ultimate 'Mother Mary' figure: an immense, centralised power that claims to know what is best for its 'children' whilst actually uprooting and destroying them.

She once noted, 'My mom was constantly destroying me, stitching me back... I just held on to the stitching-me-together part.' Paradoxically, whilst she recognises the 'stitching' or restorative effort of her mother, she allows no such grace to India.

Her lack of a protective father figure and her exposure to maternal volatility have created a worldview where protection is a myth and authority is a threat. Consequently, she naturally gravitates towards movements that seek to dismantle the 'Father-State'—the government and the military.

So, let me use Ms Roy's own 'Rule of Three' to make my point:

Does she love the environment more than the progress of poor Indians? Does she hate India more than she values the security of 1.4 billion people? Or does she hate Hindus so much that she supports Islamic terrorism under the guise of 'freedom'?

It is easy to decide.